The sunlight streamed through the white curtains, through the transparent solar cells of the

windows. The trees that grew beside the apartment in the forested city glowed green.

The light warmed Salma’s face. It warmed their kitchen as she pressed her fingers into

the dough, la masa, that had risen overnight. Salma pressed the dough with her pin and filled the interior of the empanada.

She had set the interior, el relleno, in the fridge so that the crushed tomatoes and peppers

wouldn’t run against the dough. Empanadas took time to make and disappeared from the plate

quickly, but she wanted him to have a filling lunch.

Pastissets, as he called them in Valenciano, were her grandfather’s favorite. Salma

pressed her fingers into the dough and the worn table rocked back and forth again. She tried to

not let it bother her, the fact that nothing, not even a broken table leg or a frame against the wall,

could be changed in their kitchen.

If she moved anything at all, which her grandfather never would, the sun-faded paint

would remember where it had been—darker in the spots that had been hidden.

'It’s dangerous, Salma. Leave it alone.'

Her grandfather’s hand shook as he sipped his espresso. The coffee sloshed over the

edge, but he was focused on her.

'Listen to me, Salma.'

Salma folded the edge of the pastisset over with her left hand. Her fingers twisted the seal

and curved the braided pattern along the dough.

'Escuchame.'

She placed the empanada on the baking tray and looked up at him.

Yo oyó, I hear–she wanted to say–te escucho. I hear you.

'I’m listening,' she said in English.

Her grandfather shook his head.

He turned and looked outside. He ignored the trees which moved gently by the window.

He did not see the city the way she saw it—as a city that had grown from the seeds of a

reforestation program. A city that had a root system, slowing runoff and evaporating water into

the clean air. It was an urban ecosystem that flourished.

Her grandfather still felt the sweltering urban heat of the past. On days like this one, his

mind lived in the old city. The days when he worked in the factory: when he and her

grandmother, Yaya, were building their family.

The dough ripped against the braided edge, revealing the bright red tomatoes, egg, and

the paprika-covered tuna within. She tried to pinch it together again, but the dough was wet now, and it gaped wider apart.

'The factory is dangerous. You know the stories,' he said. He frowned at the possibility

that she might be forgetting. He had lived in both worlds.

As the just transition began 50 years ago, halfway through the 21st Century, the

plastic manufacturing factory had been permanently closed. Their economy now placed value on the acts that strengthened and sustained their community and environment, rather than dividing and degrading it.

Her grandfather, like everyone leaving the factory, had a selection of work. The roles

supported the just transition, gave everyone a place in building the change. Her grandfather had

been given his pension, and he had chosen to not return to any kind of work.

Salma tried to mend the tear in the pastisset.

'When I first heard about the facility, I didn’t think it would be so bad. I had friends

there.'

Salma nodded and set the timer on the hot oven.

His head nodded gently the way it did when he was focused. Salma wiped her hands on

the sauce-stained towel and sat across from him. The beginning of his story had been different

this time; it would change how he told it.

She would always listen to his stories, even the ones she knew by heart.

‘One day we showed up to work, and my closest friend, José…’ He paused here and

frowned. ‘José P… José Pa–'

‘Well, all I know is, he was there the day before as healthy as could be, in the packaging

line like we all were,’ he said, ‘the next, he was gone.’

He blinked, looking away.

‘Something happened that night. No one talks about it, but it did.’

The breeze came in through the window and the leaves rustled. Salma reached forward

and held his hand. The smell of the pastissets wafted into her nose and she inhaled deeply.

Te eschuco, she wanted to say. I hear you. Not for the first time she wondered how it

would be different, if only they could speak to each other in a way that they both could

understand.

‘The factory consumed José. Swallowed him whole,’ he said. ‘José was going that night,

he told us, to vandalise the equipment. He was tired of the work slowly killing us.’

Salma nodded.

Her grandfather’s words were charged with accusation.

‘He was trying to make changes to the factory. Like you are now. Es la verdad.’

Salma let go of his hand. This was a memory taking shape as a story. He grasped at the

past and fit it into the feelings that remained.

She pointed at the oven.

‘Make sure you take those out after forty-five minutes. Golden brown.’

Her grandfather waved his hand at her. They both knew she would go to work and

continue leading the remodel of the factory.

It was an honor to have been chosen. All of the supervising structural engineers had

fought over this project. The first time she visited the site she understood why—the potential for

change was immense in the space.

The plans for the retrofit moved in her mind.

‘You are waking it up, and once its eyes are opened, people will get hurt.’ He shook his

head. ‘Your Yaya would understand.’

She tried to imagine the words she would say in Spanish, but the words crumbled in her

mind. She wouldn’t say it right, not the way she wanted to.

‘We’re building something from it,’ she said.

The factory was already changing, inevitably. But they would build something of its

parts. They would retrofit and imagine a future for it beyond its disrepair.

There was nothing to debate. She knew, more than most, that a building affected the

living, but it was not living. It did not consume people.

She glanced at the clock. It was her first day onsite and she didn’t want to be late. She felt

a jolt of nervousness at the prospect of the plans taking shape, of working with the crew today.

She pushed her foot into her steel-toed work boot and tightened the laces.

‘I will be careful.’

‘Pah. Careful.’ He waved his hand. ‘We were all careful. José was careful.’

She grabbed her vest and clipboard.

He turned and stared through the window.

‘Those who don’t try to remember, choose to forget.’

Salma nodded and picked up her hard hat. They would have this argument again

tomorrow, as they had for months, because he could not let her forget.

She thought of how she had stuttered over the simple word, escuchar. It separated her

from her grandfather, the gaps formed in the past.

She stepped through the door and locked it.

As she stared at the factory, grayed with decrepit edges, she knew, if any place could consume a person, it was this one.

At the very least it would haunt.

The factory building loomed over their greened city. She thought of the people like her

grandfather, stepping inside each day as she was now, waiting for change to come.

People like José Pa–. Whose story and name might never find its resolution for her

grandfather.

She glanced back to the lush green tree line that delineated their city, with their light-blue

colored apartments, and she wondered if the past world could ever be a part of this one.

The factory seemed to grow larger before her. In its dereliction, its rusted metal bones

stretched upward, casting long shadows in the bright morning. The usually cool morning felt

hotter.

Her hand shook as she unlocked the gate.

‘Salma.’

Her clipboard hit the ground.

A woman, Irene, bent down to pick it up for her.

The building contracted back to size.

Irene was the foreperson on site and the primary union representative. Salma had worked

with her on many projects before.

‘Didn’t mean to startle you.’ Irene nodded to her and began flipping through the plans.

Irene kept things to the point with Salma, and only spoke to her in English. Her family

had also immigrated to the forested city in the Northeastern United States. She knew that

Salma’s Spanish was fading within her.

Everyone in their city knew that Salma’s mom had left for the governing city when she

was young. They knew that she had only come back, years later, to leave Salma with Yayo.

‘This is a big project,’ Irene said. She looked at the schedule for the day.

Salma nodded.

‘Heat and water pumps outside by the back corner, insulation work, electrification,

windowed solar panels,’ she said.

Irene glanced up at her and gave her a quick smile.

‘With all the funding we need to do it,’ she said.

For over 40 years, their government had generated the funding for projects like this one

by taxing high-frequency financial transactions. Every time a stock was bought or sold by a

trader, there was a fee that was put toward citywide initiatives.

The financial sector could no longer accumulate immense, unequal capital, and

community projects like this one had the financing to succeed.

Salma unlocked the sliding door to the side of the factory.

The overhead lights flickered. The space had a hollow sort of feeling. It was filled with

the past. She stepped inside after Irene.

Empty space. Espacio vacio.

‘The low energy heat pumps could be connected here,’ Irene said.

Salma squatted down and pulled open the paneling.

‘It might need rewiring.’ She nodded. ‘Let’s move onto weatherisation and insulation.’

Irene made a note.

Maybe Salma had been too hard on her Yayo. She didn’t want him to think she wasn’t

listening. His stories had filled her childhood, and they had taught her about life, in ways she

could only realise in retrospect.

He raised her through these stories, in ways her parents never had.

Salma pointed to the wall and imagined it carved open for wide windows. She drew her

finger in the air around where the opening would be made.

‘This is where the windows will be. They’ll install the transparent photovoltaic glass

here.’

Irene nodded. ‘We might lose some heat to them in the winter, but the lighting inside is

important.’

They were discussing the insulation when the construction crew arrived. Their laughter

echoed into the building’s emptiness, filling it.

Salma supervised them as they operated the lifts. This crew had worked on her sites for

years. She trusted them to clear out the old building and begin building something new.

She checked the old supporting concrete slabs again. It wasn’t the low-carbon calcined

clay concrete that was standard practice now.

The crew conversed easily, moving between languages.

There was some steel rebar protruding from the side of the column. She made a note.

She caught a few words of their conversation here and there.

‘Ni pensarlo,’ someone said.

‘Claro, claro, claro.’ The group laughed.

She tried to think of what she would say to join in, but her sentences formed too slowly,

one word at a time. The conversation had already changed.

As usual, she found comfort in listening.

Irene spoke to one woman as she lifted a box. The woman pushed another metal box onto

the lift.

‘De verdad, mi abuelo trabajó en…fábrica,’ the woman said.

The woman. Her grandfather. Worked.

He worked in this…fábrica…fábrica—factory? Salma looked up at her. Irene nodded and tapped the side of the lift to drive the boxes away. Words floated toward Salma…salió…en la noche.

Salir. Left in the night.

He left in the night.

Solomente…only…una nota…a note.

Her grandfather worked in the factory. One night, he left, leaving only a note behind.

Salma pretended to make a note on her clipboard page about the ceiling. She inched

closer to the conversation.

‘Dejó mi abuela, sola con mi padre,’ the woman said.

He left…her grandmother behind, alone with her father.

Salma pieced the story together.

‘Ella dirían,’ the woman said. ‘…el guarro José.’

José. Salma stopped pretending to take notes. José Pa–?

Could it be the same person?

She thought of the look on her grandfather’s face when he told her the story this morning.

The way he hadn’t noticed the coffee staining dark against the tablecloth.

Irene was changing the subject, and Salma wanted to tell her to stop. She needed to

resolve her grandfather’s story. If they would find him hidden in a story with a different end.

Irene was moving past it, talking about the yellow tape on the boxes. The woman walked

with her. They laughed.

Salma struggled to piece together the words. She would ask the question that might bring

Yayo some peace.

Her words were stuck in her throat. The language broke, again, within her.

But still, Salma lingered near Irene. She could not look away. A question began to form,

above her other thoughts.

Qué, what—no—which, cual es tú…last name. Apellido. ¿Cuál es tú apellido?

The question was simple. What is your last name? Cual es tú apellido. She chanted it in

her head, repeated it like it was a statement. Cual es tú apellido.

She opened her mouth, and it was dry. Her tongue moved strangely in her mouth.

Cual es tú apellido.

She needed to say something. This language was a part of her. She would find the words

to speak.

‘Cualestuapellido?’ she said.

The words stuck together and rose in pitch at the end.

Irene glanced at her with her eyebrows together. She pointed to herself in question.

Salma shook her head and gestured to the woman beside her. She pressed her hand

against her clipboard. There was no getting out of it now.

‘¿Cuál es.’ Salma slowed herself. ‘¿Tú apellido?’

The woman flushed.

The question was too direct. It had the wrong tone. Salma didn’t want the woman to think

the supervising engineer was taking her name down for some other reason.

She stumbled over her words. ‘Yayo, mi abuelo, mismo…’ she said. She wasn’t making

any sense. She needed to slow down. Salma thought of the words the woman had used earlier.

They were at the front of her mind.

‘Mi abuelo trabajó…' She could finish the sentence. ‘…en esta fábrica.’ She said it

again, this time with the accent in the right place. ‘También.’

The woman nodded. Irene’s face broke into a smile.

They understood what she was trying to say.

The room brightened and expanded. The past could not consume them now. She pictured

Yayo’s face when she told him this story, about how she had found the answer they were looking

for in a language she rarely spoke.

‘Ahh, vale,’ the woman said. ‘Mi abuelo no trabajó en esta fábrica.’

She paused, giving Salma the time to process it. Salma’s heart fell.

The woman’s grandfather, José, did not work in this factory.

‘Él trabajó en una fábrica en la ciudad de la energía eólica.’

Salma eyebrows drew together. He worked in the factory in the city of the energy…

The woman understood her confusion. ‘Viento.’

Wind. The wind energy city. This José had worked in a factory in the wind energy city.

He was not José Pa-.

Salma felt a tap on her shoulder. A member of the crew glanced at the open factory

garage door.

‘I am sorry to bother you, but there is an old man wandering around the premises,’ he

said. “‘ told him that this was a closed construction site, but he just waved his hand at me.’

Salma’s heart sank, and she walked towards the door. The resolution had not been found.

Her grandfather stood there and stared blankly at the factory. The sun had begun its descent in

the sky, casting shadows across his face. In his hands, he held a glass container.

Salma opened her mouth. She had to tell him that he couldn’t be here.

But there was something in the way he was standing. He stood in the face of the factory

that he swore he would never return to, the place that was both empty and filled with the past.

He lifted his hand.

‘I brought you some pastissets.’

The light reflected off the tears in his eyes.

Salma took the container and opened it. She gently broke the pastisset with the cleanest

braid, where the dough cleanly met the filling. The savory center glowed in the light.

She offered him the other half.

The filling was still warm on the inside. The flavors moved together in harmony, the

flaky exterior opening to something soft and cherished.

They ate quietly until the doughy corners disappeared from their fingers.

‘This city was built around the factory. I, we, depended on it,’ he said.

They began to walk around the perimeter of the factory.

‘Harmful, yes, especially when you see it with today’s eyes, but it gave us work.’

They paced slowly forward, step by step. Her arm supported his.

‘When the city changed, the factory was closed.’ He paused. ‘It was abandoned.’

A new film of tears rushed to his eyes, reddening them.

‘The factory closed, and your mother left the first time.'

Salma’s eyes filled.

‘The city decides the factory will be retrofitted, and then, your Yaya passes.’ His voice

caught.

Her grandmother had decorated their apartment. She had chosen every frame, and the

wooden table that rocked back and forth. She passed away six months ago.

‘And now you’re here and the factory changes again—’ Her grandfather stopped

speaking.

A tear dropped down and fell into the soil, watering the ground. She could have cried for

him, right then and there. Cried for all he had lived through, cried for all that was no longer here.

A few more tears fell.

Salma inhaled deeply, smelling the tree pollen that floated through the air. She felt the

warmth of the sunlight against her cheek.

She lifted her hand in the direction of the factory. She would ask him something she

hadn’t thought to before, not when she accepted the project, not in the silence that stretched

between them.

She took his arm in hers.

‘Would you like to hear what the factory will become?’

He turned towards her with his eyes still bright.

‘Sí,’ he said.

Salma chose her words carefully.

‘The center will be a community space. They will offer free childcare.’ She gestured to

the other side of the rusted metal building. ‘And this side will be for adult education courses.’

She talked of the plans that they had for art classes and poetry. She talked about how the

space would be opened up for concerts on the weekends.

The wrinkles between his eyes smoothed.

They walked around the back of the factory.

‘This is where the murals will be painted in bright colors, the artists commissioned from

every city, all brought to re-envision the metal walls.’

Her Yayo’s head nodded slightly in the way it always did when he was focused.

‘The community garden will be planted here, between the trees,’ she said. Her Yayo

smiled and gazed up at the low branches that hung over them.

The trees waved their branches slowly in the air. Their gentle hush soothed the space

between them. The warm air passed through Salma’s hair, and it settled calmly around her.

Her grandfather squeezed her arm.

‘There will be work,’ he said. He gazed at the world around him. ‘But I can see how

beautiful it will be.’

They stood side-by-side in the face of the factory. There would be work in building the

future. Salma smiled. It would be the work of her life.

In the fading light, the factory did not seem so abandoned. The building glowed with the

life it could have. The crew laughed as they moved in and out of the doors. Blades of grass grew against the concrete and broke free through the cracks.

A tear, una lágrima, fell from her grandfather’s eyes.

Kiera Alventosa is the Environmental Health Organizer for Clean Water Action, and where she works with environmental justice communities on the issue of lead in drinking water. She holds masters degrees in Nature, Society and Environmental Governance from the University of Oxford and in Writing from the University of Warwick, where she specialized in environmental fiction. During her undergraduate degree at Amherst College, she was the recipient of the Academy of American Poets University Prize in 2020 and the Peter Burnett Howe Prize for excellence in prose fiction in 2021. She is currently looking to publish her manuscript and can be contacted at https://kieraalventosa.wixsite.com/kieraalventosa

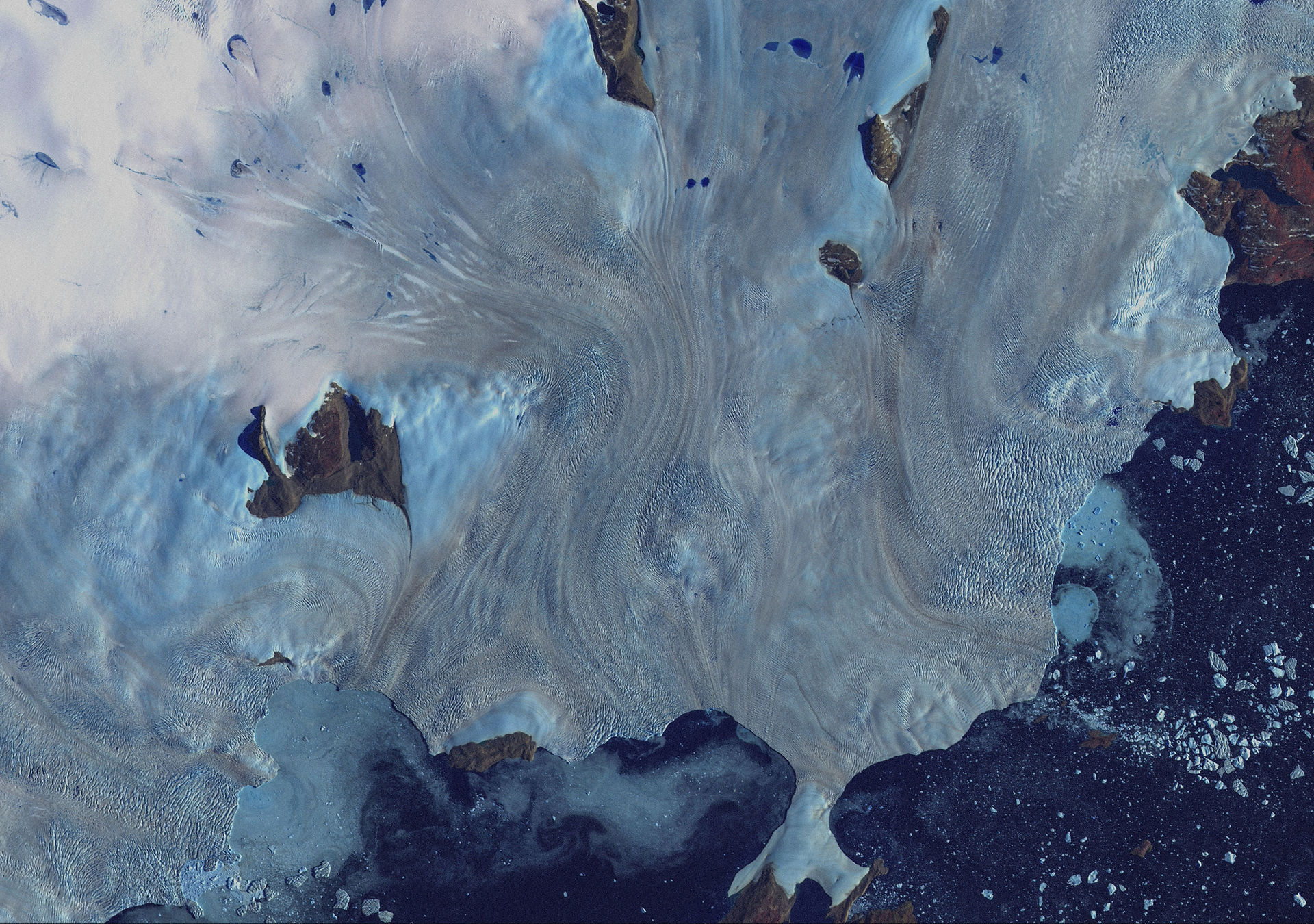

Artwork by Karolina Uskakovych— a designer, artist, and filmmaker from Kyiv, Ukraine. Karolina is a co-founder of the Uzvar_Collective and Art Director for the magazine Anthroposphere: The Oxford Climate Review. She is also artist-in-residence at Re(Grounding) programme as well as the Digital Ecologies research group. Her current research explores traditional ecological knowledge in relation to gardening in Ukraine.

コメント